Badass from the Past: Mary Seacole

- Emily Sinclair Montague

- Feb 7, 2019

- 4 min read

Badass from the Past is a monthly series spotlighting astonishing historical women whose accomplishments have not been given their due. They changed the narrative, and now we're amplifying their stories. For more articles, see the tag #BadassFromThePast.

This month’s Badass from the Past is the marvelous Mary Seacole! A woman of many talents, she is best known for her services as a nurse during the Crimean War (1853-1856).

Born Mary Jane Grant in 1805 to a Scottish officer and a free woman of African descent in Kingston, Jamaica, Mary began her nursing education by assisting her mother at her boarding house for invalid soldiers. Diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and Yellow Fever were common in Jamaica at this time, and Mary received valuable firsthand knowledge and practical skills while treating the ill.

For a time, Mary was hosted by a wealthy patroness of her mother’s. For a time, Mary was educated and lived alongside the patroness’ children. When the patroness died, Mary returned to live with her mother and resumed her initial duties as a nurse and co-operator of the boarding house.

Since Jamaica was under British rule from 1655 to 1962, Mary's rights as a mixed-race Creole woman would have been limited. While she and her mother could own their own property, they could not vote or enter official professions. Running the boarding house and performing occasional house calls to visit the sick were their only sources of income.

In 1863, Mary Grant married Edwin Seacole. They opened a provisions store, which experienced little success, possibly due to Edwin’s “weak constitution” and tendency to fall ill. The couple returned to live at the boarding house, and both Mary’s mother and Edwin would both die in 1844. Mary never remarried, citing a lack of desirable suitors. After the boarding house burned down in the Kingston Fire of 1853, Mary rebuilt the family business and continued her life with characteristic determination.

Her status as a single woman did not stop Mary from fostering her love of travel and adventure. Before her marriage, she explored parts of the Caribbean, including Haiti and Cuba, on her own. Around 1850, Mary’s brother journeyed to Panama to open a hotel and store. At the time, Panama was considered a lawless frontier and merely a stopover point for Americans traveling to gold rush towns in California and Mexico. Mary cited her insatiable wanderlust as her inspiration for joining her brother in the town of Cruces. She left Jamaica and undertook a harrowing journey only to find that her brother’s “established” hotel and store were little more than a run-down hut and mess hall.

Never one to let hardship slow her down, Mary set to work aiding her brother in operating his business. She took up the mantle of nurse once more, treating the injured and victims of a cholera epidemic that swept through Cruces. Although she contracted cholera herself, Mary fought through the epidemic and saved many lives.

Mary encountered blatant and frequent racism from Americans in Cruces, which she mentions in her autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. Mary did manage, however, to gain a measure of respect, affection, and status in the community. In her narrative, Mary describes her life and nursing experiences in Panama, including witnessing everything from knife fights to catastrophic flooding.

After her South American adventures, Mary returned to Jamaica. She nursed the sick and dying through a Yellow Fever epidemic in Kingston before voyaging to London, where Mary learned of the horrors British soldiers faced on the Crimean War front. Undersupplied and overwhelmed by the well-trained Russian army, British soldiers were dying in the hundreds from injury and disease. Like many women of the time, Mary was moved by the suffering of her English “sons.” Mary tried applying as a nurse through the British War Office, but gave up after being bounced from department to department on a wild goose chase. Mary then applied to become a nursing recruit within Florence Nightingale’s organization, but was rejected, likely due to racism and Mary’s lack of social connections in London.

Undeterred, Mary blazed her own path to Crimea. She became business partners with Mr. Day, an acquaintance, and the two set out to open a provisions store and hotel near the front lines in Sevastopol. After a difficult journey fraught with thieves and inclement weather, the two finally arrived in the city of Balaclava and began setting up The British Hotel. Also known as Spring Hill, the hotel and store became a popular spot for British, French, and Turkish officers seeking rest, comfort, and a hot meal. In addition to running the business, Mary also nursed any who needed her aid.

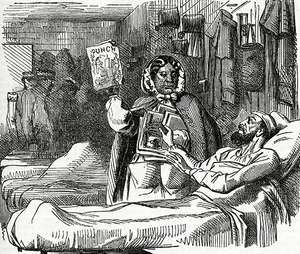

As a single woman and nurse on the front lines of a war, Mary took extraordinary risks to care for soldiers. She was frequently under fire, exposed to Russian cannons and bullets, and was injured more than once in the line of duty. Mary fought outbreaks of cholera and dysentery, diseases with which many white doctors were unfamiliar treating. Her remedies were considered more efficacious than the Western medicines typically used by professionals like Florence Nightingale. Mary became known to soldiers and officers as “Mother Seacole,” and was held in high affection for her tenacity, bravery, and unfailing compassion. Under Mary’s care, Spring Hill became a true home to soldiers who were thousands of miles from their homes and families.

Although Mary was successful in providing comfort and succor, the hotel was a financial failure. After the war, Mary returned to London bankrupt. Her efforts in Crimea had cost her everything. Moved by her plight, a group of soldiers she had nursed and cared for banded together to aid Mary financially. With their encouragement, she wrote and published her autobiography, and lived comfortably until her death in 1881 at the age of 76.

Mary Seacole was mainly forgotten by history until 2004, when a U.K. poll recognized Mary as #1 of the "100 Great Black Britons." A statue of Mary stands at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, and her story lives on through her autobiography and the lives she saved.

Is there a Badass from the Past you’d like to see featured on The Fem Word? Let us know in the comments section or on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram!

Comments